(AFRICAN?) AMERICAN DASHIKI

Dashiki shirt made from heavy, strip woven cloth - African

African Textiles: Color and Creativity Across a Continent, p102

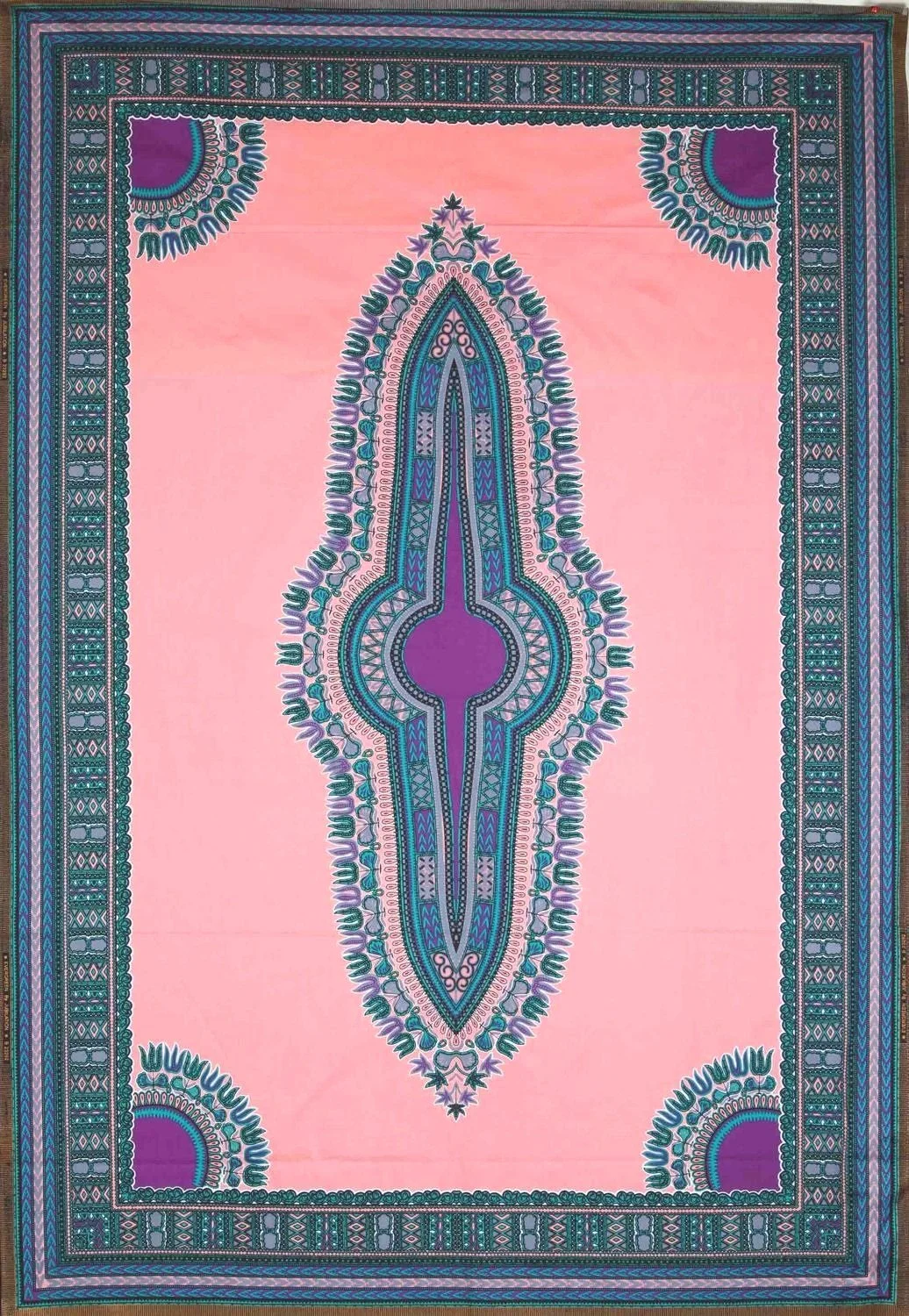

Dashiki pattern printed on lightweight, factory woven fabric - Dutch

Dashiki shirt made from dashiki fabric - American

The dashiki style shirt, a loose hip-length garment with an open neckline and central pocket, was bought to America from West Africa by peace corps volunteers during the early 1960’s. The American term dashiki was coined from the Yoruba dàńṣíkí meaning ‘work shirt’, which was itself coopted from the Hausa dan chiki meaning an ‘inner garment’ intended to be worn beneath a much grander robe. The origin of the shirt was likely an early influence of Arabian traders who brought Islamic religion and culture to Africa.

The dashiki shirt is distinct from what is colloquially known as the dashiki textile print. Dashiki shirts can theoretically be fabricated from any textile but in West Africa they are traditionally made from hand-loomed, strip-woven textiles with no printed designs which are much heavier than the machine woven, factory printed textile bearing the name dashiki in America.

West African participation in the international import and export textile trade began in the 11th century however it was in the 1800’s that a series of events coincided to create what would become the phenomenon of African wax print: (i) The British and Dutch colonized Indonesia. (ii) European factories developed the capability to mechanically reproduce traditional hand-printed Indonesian batik textiles with the goal of selling them in Indonesia (iii) The Indonesian market rejected the textile (iv) An economic upturn in west Africa prompted a surge in demand for printed textiles (v) The idiosyncratic irregularities of wax print ‘bubbles’ and ‘crackle’ captivated the West African market.

By the early 1900’s British and Dutch textile manufacturers had started adapting Indonesian designs to align with African aesthetic principles, though the legacy of Indonesian themes is still present in wax print today. Further technological developments during the 20th century also led to the introduction of java and fancy print which were wax print variations of lesser quality and price. Paradoxically, the very textiles once deemed by Indonesians to be inferior imitations of genuine wax batik are now considered “guaranteed real” wax in Africa - premium quality products compared to java and fancy print.

The dashiki textile, originally named Angelina, was a java print designed in 1963 by Toon van de Manakker - an employee of the Dutch textile manufacturer Vlisco which caters to Central and West African markets. Van de Manakker drew inspiration from 19th century Ethiopian tunics when designing Angelina which was one of numerous styles the company produced each year to meet a constantly fluctuating demand for novelty.

19th century hand embroidered Ethiopian tunic made from Manchester calico imported from England and silk imported from China.

Property of The British Museum

Dashiki print textile, factory made in China

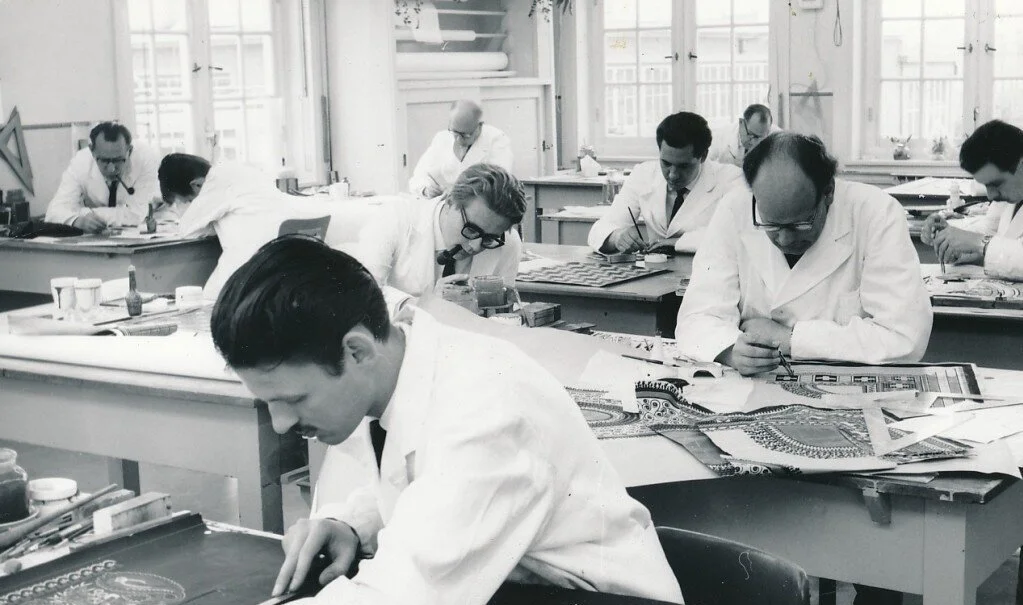

The angelina design in production at Vlisco headquarters in Helmond, Netherlands, 1967

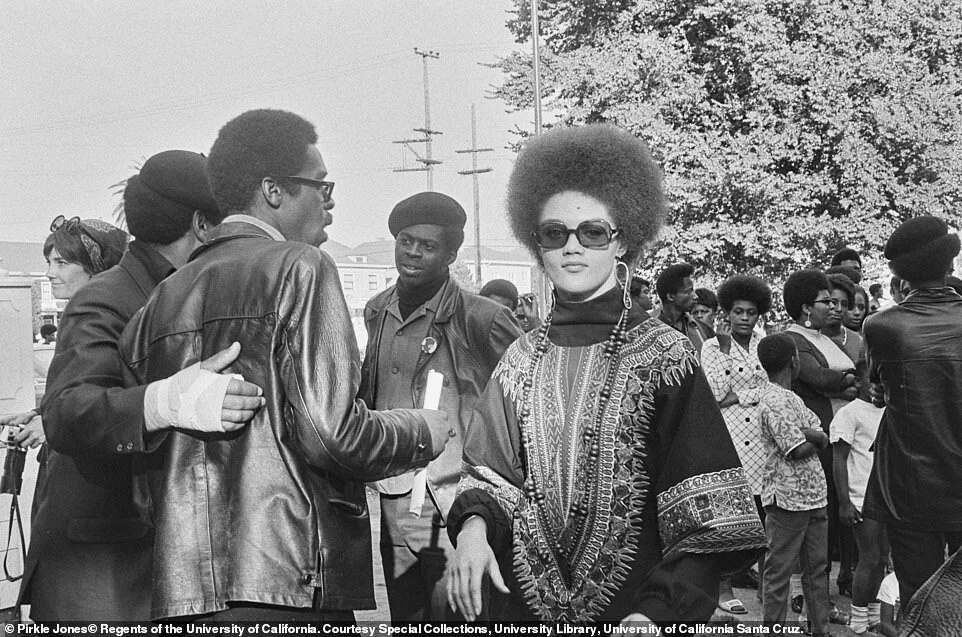

In 1967 in a Brooklyn apartment, seamstress Mabel Benning constructed an African print tunic which was to become a symbol of the African American Black Power movement.

American law professor Kathleen Cleaver wearing a dashiki at a Black Panther rally, 1968

Mabel’s husband Jason Benning, a professor of Black history, established New Breed Clothing Ltd with cofounders Milton Clarke, Howard Davis, and William Smith driven by the popularity of the tunic his wife created. New Breed opened their first storefront in Harlem and a factory in Clinton Hill soon followed by boutiques in several American cities and partnerships with department stores such as Sears and Bloomindales distributing dashikis across the country. The founders’ mission was to be “to uplift the black man by working toward economic independence and developing pride in his heritage”[1]. New Breed clothing was worn by numerous African American celebrities and featured in TV, film and stage performances during the two years the business was in operation.

New Breed fashion boutique in Harlem, 1968. Yale Joel/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

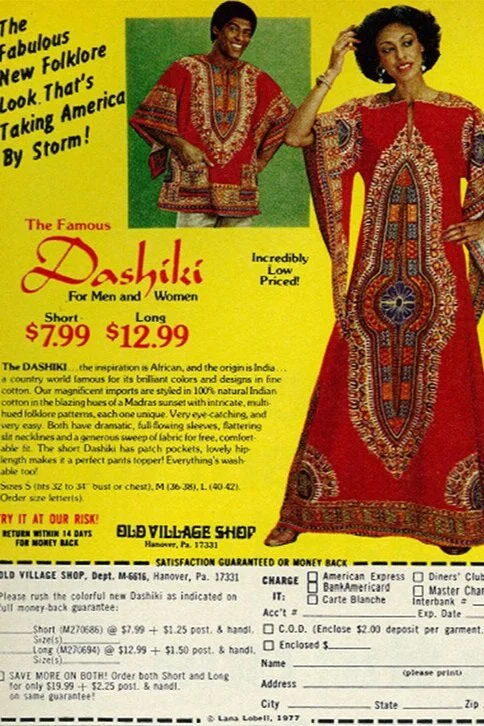

The dashiki rapidly extended its reach beyond initial associations with black heritage to become a leitmotif of mainstream bohemian style. The explosive demand encouraged Southeast Asian manufacturers to mass-produce replicas, undercutting Vlisco’s inflated price. The trend waned in America in the late 1970’s followed by a 21st century resurgence in contemporary clothing styles.

Ebony magazine advert 1977

Prom dress by Kyemah McEntyre 2015

Christian Dior Spring/Summer 2019

American dashiki shirts were fabricated from imported Southeast Asian imitations of an original Dutch design made for export to West Africa. The Dutch original was both a simulation of Ethiopian embroidered shirt designs made from imported British and Chinese materials and a failed attempt at reproducing Indonesian batik designs. Given that Angelina is java print rather than ‘genuine wax print’, it is also in essence a cheap imitation of itself. This globetrotting textile has an origin story which barely contains a whisper of West Africa and the question of its authenticity should be quite contentious.

1970’s dashiki made in Pakistan

The popularity of dashiki print also ebbed and flowed in Africa. Unfortunately, market dynamics there are not well documented however its appeal undeniably intensified over time and spread over greater territory. The appetite for dashiki print in Africa appears to have been relatively mild when first introduced but absent documentation I can’t be certain exactly how it was perceived or worn. It is possible there was a style of shirt or blouse worn in West Africa during the mid 1960’s which closely resembled the one to become popularized in America shortly afterwards though there no evidence that this was the case. Even if we assume there was an African precedent for the precise combination of shirt + textile adopted in America, this still begs the question of whether it shared the same symbolism on both continents. The shirt became an emblem of African heritage in America but was it an emblem of African heritage within Africa at the time? I have not seen this question addressed in the scant texts which cover the history of Angelina but I believe it is of at least equal, if not greater, significance to the question of the garment’s authenticity as its geographic trajectory.

I imagine that a work shirt or inner garment made from comparatively flimsy, budget priced, factory printed java would not have been considered a suitable canvas for heralding pride in one’s heritage in a West African context therefore the combination was an improbable vehicle for transmitting the message it was later assigned. Even if this were not the case, we still need to evaluate whose ancestry the dashiki print could possibly have represented? Each West African tribe has their own unique textile customs and there were no paradigms for ‘national textiles’ let alone ‘a textile of the continent’. People express pride in their heritage by wearing hand woven textiles affiliated exclusively with the tribe each individual belongs to, as exemplified by political dignitaries of the past and present, regardless of whether or not it reflects the national cultural majority.

Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, c. 1955

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Prime Minister of Nigeria, 1961

Milton Marga, Prime Minister of Sierra Leone, 1962

Given that connections between cloth and identity derive from tribe, I find it doubtful that West African people considered dashiki print (which belonged to no tribe at all) to be symbolic of their identity. It is far more likely that the local perception of dashiki was simply that it was pretty, and thanks to being a European import, exotic. Which leads me to reason that the classic African American dashiki of the late 60’s was not considered representative of African culture within Africa but instead was an impression of African heritage conjured up in the American imagination.

I suspect the appeal of the dashiki textile would have extinguished quickly in Africa, like thousands of other factory printed textile designs which have since vanished from collective memory, were it not for its prestige in America. Perhaps it was ironically the Americanness of this African American clothing style which ignited and fueled its lasting allure in Africa by bestowing it with an elevated status. The African America dashiki might be a rare episode in fashion history where an erroneous perception of African authenticity galvanized a motif into such enduring popularity that it eventually became authenticated as bona fide African culture.

Self-portrait by studio photographer Felicia Abban, Ghana 1965

A rare example of angelina worn in Africa prior to its American translation. Abban said that for her the meaning of angelina was “looking sweet and sophisticated”

[1] P Antonelli and M M Fisher, ITEMS: Is Fashion Modern?, Museum of Modern Art, 2017 p 99

C Spring and J Hudson, Silk in Africa, University of Washington Press, 2002

S Gott, K Loughran, B Quick and L Rabine (eds.), African Print Fashion Now! A Story of Taste, Globalization and Style, Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2018

A Grosfilley, African Wax Print Textiles, Prestel, 2017

C Spring, African Textiles Today, Smithsonian Books, 2012

A Lynch and M Strauss (eds.), Ethnic Dress in the United States A Cultural Encyclopedia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014

P Joseph, “Dashikis and Democracy: Black Studies, Student Activism and The Black Power Movement”, The Journal of African American History, Vol. 88, No. 2, The History of Black Student Activism (Spring, 2003), pp. 182-203

P Antonelli and M M Fisher, ITEMS: Is Fashion Modern?, Museum of Modern Art, 2017

K Mtshali, The revolution will wear a dashiki: How a 1960s Harlem couple popularized Afrocentric fashion and built a community where black power thrived, www.timeline.com, 2018

Talking about the New Breed with Howard Davis, www.medium.com, 2018

L Bowles, “Dress Politics and Framing Self in Ghana: The Studio Photographs of Felicia Abban”, African Arts Vol. 49 No. 4 Winter 2016, The MIT Press

J Gillow, African Textiles: Color and Creativity Across a Continent, Thames and Hudson, 2003